06 Feb The Maritime Underground Railroad

Its Black History Month, and this time of year, we here at Providence try to shine a light on black maritime history. This #TallShipTuesday we introduced the topic of the Maritime Underground Railroad. This aspect of the Underground Railroad is often overlooked in schools, yet makes up 70% of all published slave escape narratives.

The Underground Railroad was an intricate network of abolitionists, formerly enslaved people, and even those that were still held captive in the south that worked together to help black freedom seekers escape north. By its nature, this network was secretive, and therefore hard to pinpoint specifics. This means there are many dedicated researchers who must work tirelessly to uncover these secrets. We know about the maritime underground railroad from advertisements about escaped slaves speculating a maritime route, from some of the surviving first hand account of freed african americans, abolitionist newspapers, laws and regulations of the time, and by looking at the geography of black communities and settlements in the north.

Where were the “stations” of the Maritime Underground Railroad?

Cheryl Janifer Laroche and her work on the Geography of Resistance illuminates some interesting parts of the maritime underground railroad. One thing that is commonly found in her research is that many stations (stops along the figurative railroad) were in black churches. Many of these churches were located along waterfronts and were places that escaped black folks could safely continue on their way to freedom. They were waypoints along rivers that conductors could use. These conductors were folks who helped facilitate the movement of freedom seekers. Important figures like Harriet Tubman, one of the most well known conductors on the railroad, helped save thousands of people. Many of these conductors operated along waterways. Maritime conductors were often found in large ports in the deep south, along rivers between free and slave states, and the Great Lakes.

Why would Freedom Seekers use Maritime Routes?

Overland escapes had to happen very close, within a few miles of the border, of a free state. Maritime escapes allowed for folks in the deep south to also have a chance at freedom. Maritime journeys were one of the fastest and safest methods to freedom. Boats were much faster than overland passage with fewer places that these freedom seekers could be discovered. 3 miles offshore was the boundary to international waters at that time. Once past that point, many could breathe a little bit more easily as the hardest part of the escape was mostly over.

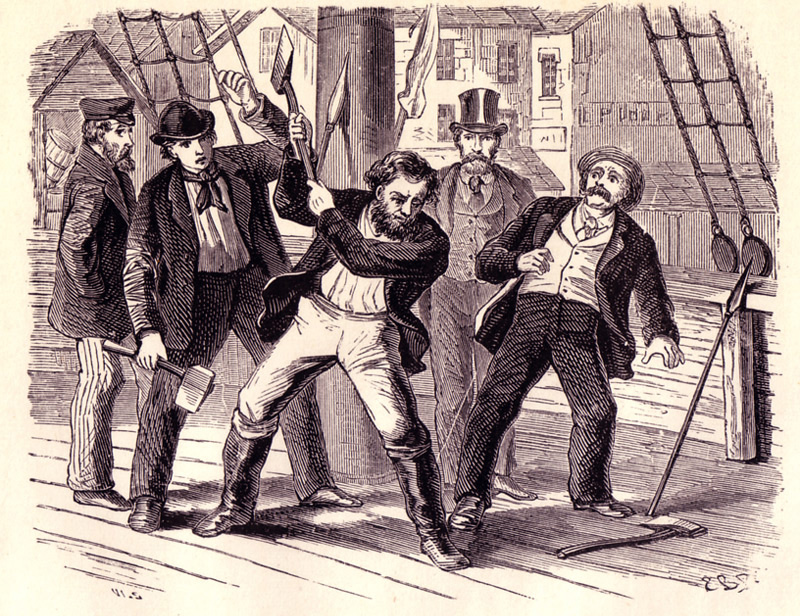

As this became an increasingly popular method of escape, more laws and regulations were passed to crack down on the conductors along the coast. More mandatory inspections of ships were performed and the penalties for those assisting in the escape of “property” to the north were harshly enforced. For black folks this was a capital punishment for them and possibly even their families. White folks more commonly faced fines and imprisonment. Regardless of the risk, there were hundreds and thousands of people willing to risk their lives to bring freedom seekers to safety.

Who were involved in Maritime Escapes

There were many possible routes that freedom seekers took from the south. freedom seekers across the river in flat boats. One conductor, John P. Parker was active along the ohio river. He born into slavery in Norfolk, VA and after freeing himself, dedicated his life to helping others escape. He was thought to have helped hundreds of escaped slaves flee to freedom across the Ohio River from Kentucky. Parker would take his flat boat in the middle of the night. Parker and his neighbor, John Rankin, worked together with other abolitionists in the area to send those e ferried to safe houses once in the north

Major ports were another place conductors worked tirelessly to assist black folks to the north. Virginia Waterways were incredibly important in the Underground railroad. One of these ports, Norfolk, a major port city in Virginia had everything from schooners to steam ships. Plantation owners trained almost all of the enslaved men on their plantations to be watermen. Thus, slaves operated all kinds of boats and performed specialized duties onboard ships. They were carpenters, shipwrights, blacksmiths, pilots and more. They were an integral part of the labor on and around ships. This meant that laws couldn’t ban black folks from being in these ports at all hours. It also meant that it was a crucial part of the underground railroad.

Several of these conductors worked within these systems in place, including Henry Lewey. Lewey, also known as “Bluebeard” was enslaved while he worked as a conductor in the Underground Railroad until 1856 when he escaped after word got out of his activities. he worked with William Bagnall to move escaped people to the north.

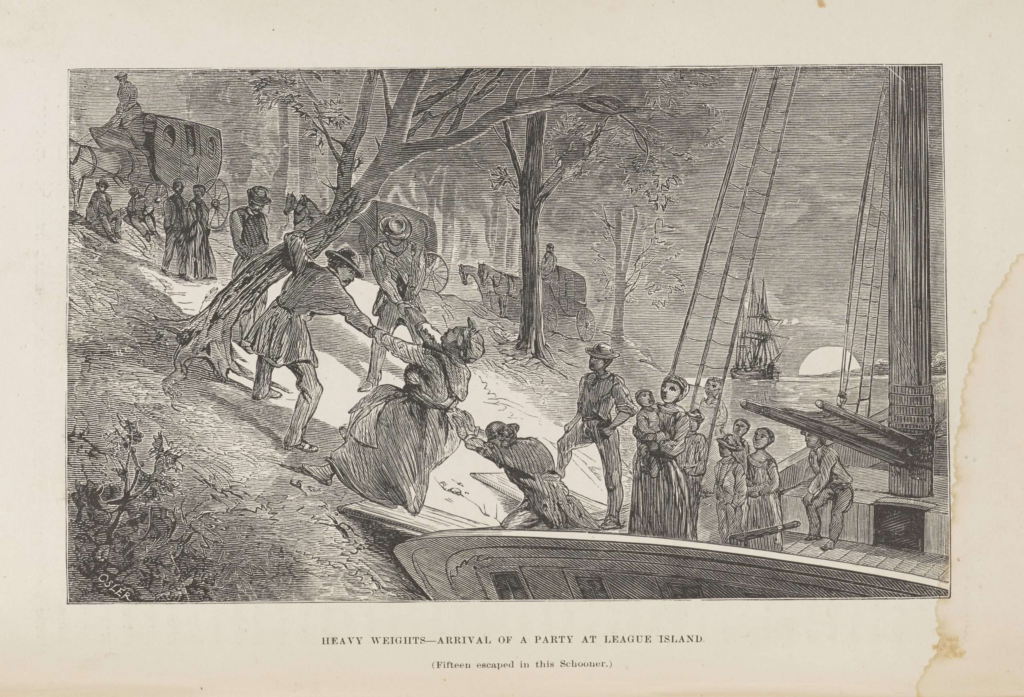

Captains would have secret compartments on their ships to hide escaped african americans. Captain Alfred Fountain had a compartment he could ferry 22-25 people on a journey to northern ports. Crew or stewards could smuggle folks into the boiler room for these journeys. It could be cramped with little to eat or drink, but at least would not be a long and treacherous trip.

Citations

American Women and the Underground Maritime Railroad: https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2015/07/maritime-underground-railroad.html#google_vignette

The Great Lakes and the Underground Railroad: https://research.lib.buffalo.edu/greatlakes/underground-railroad

The Boston Maritime Underground Railroad: https://www.nps.gov/articles/maritime-underground-railroad-in-boston.htm

Engraving of the escape of freedom seekers published bt William Still in 1872: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/10027hpr-9bb3d4f0da09edb/

Library of Congress Discussion: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIb70kWjzxc

The Underground Railroad in VA: http://www.racetimeplace.com/ugrr/history2.htm

Bluebeard the Conductor: https://www.pilotonline.com/2020/02/12/blue-beard-norfolks-greatest-conductor-on-the-underground-railroad/

Cassandra Newby-Alexander Lecture: https://virginiahistory.org/learn/virginia-waterways-and-underground-railroad

John P. Parker, Conductor, on the Underground Railroad: https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6232/“To Feel Like a Man”: Black Seamen in the Northern States, 1800-1860: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2936594

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.